Originally posted 10/25/23

Since I teach courses in Religious and Jewish studies at the university where I work, I was asked to be a roundtable discussant at a teach-in on the current conflict in the Middle East. The idea for the event was to have faculty members from a variety of disciplines (Religious Studies, Political Science, Journalism, Economics, Art History, World Languages and Cultures, Geography, etc.) offer a brief intro to their disciplinary perspective on the conflict and then lead a conversation with the 7-9 students at the table. After about 20 minutes, students would move on to another table and topic, participating in three conversations in the 1.5-hour event. Around 250 students attended and the conversations, according to most of the discussants, were fruitful.

On Wednesday morning, I was not looking forward to the table discussions. The day before a hospital in Gaza was bombed and there were conflicting stories about the source of the missile. This made the situation even more raw and complicated than the day before. Another colleague from my department shared a similar sentiment, wishing that there weren’t conflicts like this to discuss, and we talked about how these kinds of events are ultimately what we are here to do—the religious studies professor’s raison d’etre. Among our responsibilities as scholars of religion is to complicate how religious worldviews are constructed and contribute to a world filled with conflict, oppression, and violence. Of course, knowing this does not make our job any easier.

Honestly, I was anxious about the teach-in because, as someone not immediately connected to Israel/ Gaza but with friends and colleagues with deep connections in both places, I was afraid of misrepresenting the motivations of others. I was wary of causing harm by misspeaking. However, as I waited for students to come to my table, I realized that probably the most authentic thing I could do was to speak out of my own experience and from my own social location. I didn’t scrap my topic, “Ancient Claims to and Conflicts over the Land,” but I tied this to the Christian appropriation of Jewish sacred texts about the “promised land” and Christian supersessionism.

As someone who grew up in an evangelical Church, I have heard all my life that God blesses whoever blesses Israel and curses whoever curses Israel. Even though the biblical texts cited for this idea, Genesis 12 and Numbers 24, predate the modern state of Israel, evangelical Christians seemingly see these texts as a foundation for US foreign policy. In fact. according to a 2013 Pew Research Center poll, the percentage of US Christians who believe that Israel was given by God to the Jewish people was higher than among US Jews. And, while 55% of Christians overall believed this, 82% of evangelical Christians reportedly held this view. A more recent poll suggested that evangelical Christians in the US were more approving of Trump’s policies toward Israel, which include moving the US embassy to Jerusalem and recognition of Israel’s claim to the Golan Heights, than Jews in the US. When we consider who in the US demands unquestioning support of Israel, we need to look at evangelical Christianity.

Evangelical Christian support of Israel is not altruistic. It does not, for the most part, emerge out of respect for the shared history between Jews and Christians nor does it reflect a genuine concern for Jewish religious beliefs or cultural traditions. I’m not suggesting that individual evangelicals don’t genuinely care for their Jewish friends, family, and colleagues. Rather, I am saying that evangelical Christianity, as a tradition, treats Jewish control over Jerusalem as a necessary condition for Jesus’ return at the end of time. Jesus’ return, moreover, will inaugurate a thousand-year period in which faithful Christians will reign as kings alongside Christ (Rev 20:4-6). Desire for this millennial kingdom is a primary motivation for evangelical interest in Israel as a nation.

Even though many evangelical believers attest to being “friends of Israel,” they simultaneously believe that Jews will recognize Jesus as the Messiah. In Armageddon: The Cosmic Battle for the Ages, an installment in the Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, a character explains, “When Jewish people such as yourself come to see that Jesus is your long-sought messiah, you are not converting from one religion to another, no matter what anyone tells you. You have found your messiah, that is all.” In other words, Jews will come to recognize that they were wrong. Personally, I wouldn’t count this as being a friend of the Jewish people or of Israel.

One of the things I find frightening about evangelical responses to the current conflict is the prevalence of eschatological (meaning things about the “end-times”) thinking and language to describe the situation. Evangelical pastor Max Lucado published an op-ed in which he cast the situation, along with the war between Russia and Ukraine, in apocalyptic language. These are the “wars and rumors of wars” that precede the second coming of Christ. “Nation will rise up against nation and kingdom against kingdom” (Matt 24:6-7). So, Lucado calls his audience to repent and accept Jesus and, most importantly, “pray for Israel.” Even though Lucado nods to the innocent in Gaza, the focus of his is on Israel, presumably a Jewish Israel since he describes Israel as “special to God” because of God’s covenant. which was made with Abraham. There is little or no recognition that Israel includes non-Jews. One wonders whether the call to “pray for Israel” means one should pray for the healing of those injured by Hamas and for the return of hostages or for their eventual “conversion.”

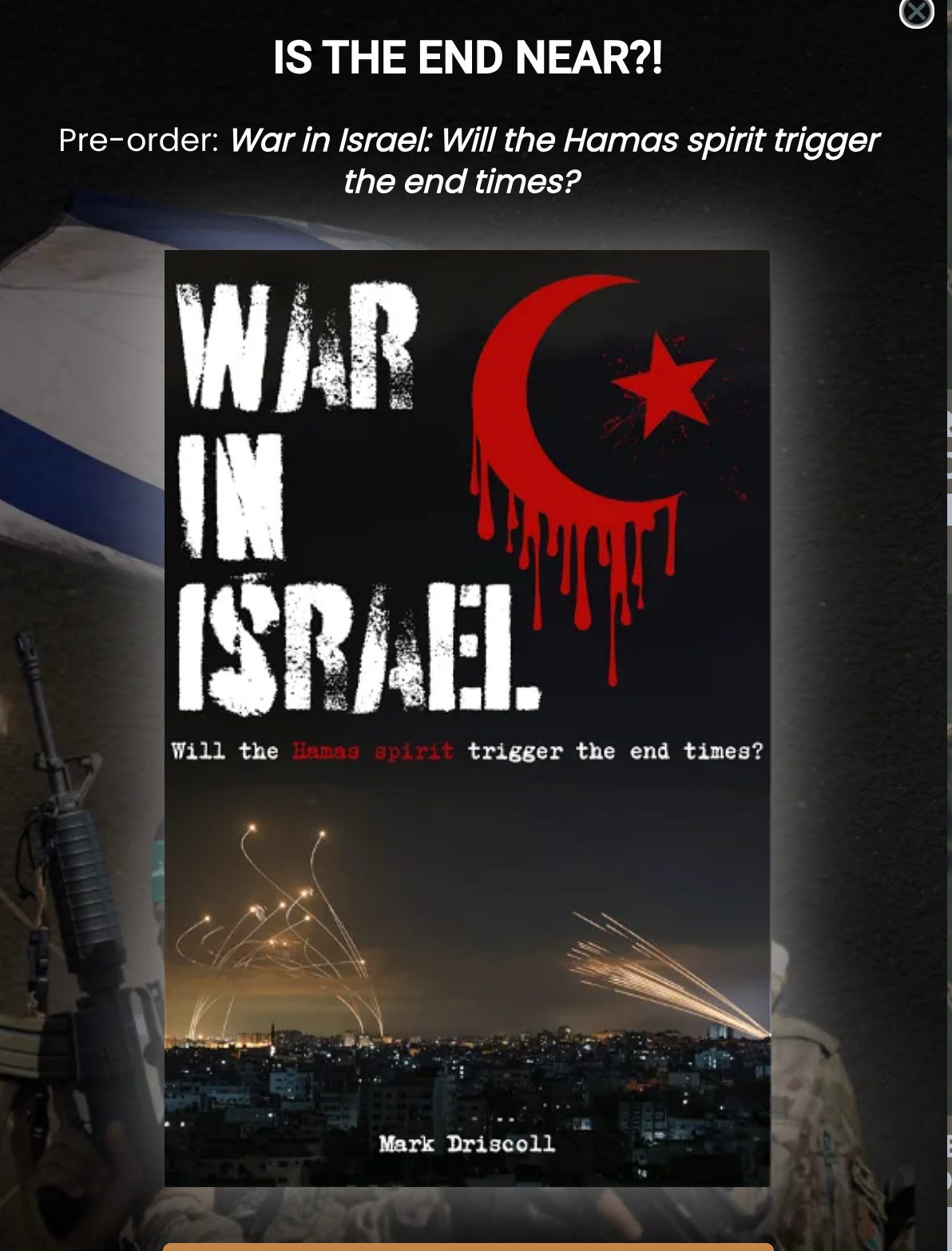

Even more disturbing is the perspective revealed in a “pop-up” ad on evangelical preacher Mark Driscoll’s webpage. Not only does Driscoll suggest that the current situation in Gaza might be a harbinger of the end times, but the use of “spirit of Hamas” is coded language suggesting that the organization is evil and satanic. The depiction of the crescent moon dripping blood underscores this. The attacks on Israelis by Hamas were brutal and horrifying, but casting the movement as a spiritual evil completely dehumanizes members of the organization and those connected to it. These actions were horrific, but I believe people are not evil. Compare Driscoll’s characterization of Hamas to the gesture made by Yocheved Lifshitz, the 85-year-old Israeli hostage who grasped the hand of one of her former captors upon release and uttered “shalom.”

In addition to predicting the coming of the end, The description of Driscoll’s book refers to “how to be prepared for a potential attack on U.S. soil.” Clearly, the concern here is not with those killed or taken hostage, not to mention the people in Gaza who suffer as a result.

Even though US politicians try to direct their language at Hamas and not Gaza or the Palestinians more generally, there are telling “slip-ups.” The most notable came from Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, a Southern Baptist, who revealed his true thoughts on the situation when he said on Fox News, “We are in a religious war here, I am with Israel. Whatever the hell you have to do to defend yourselves; level the place.” Graham’s reference to a “religious war,” perhaps a nod to the Islamic identity of Hamas, also reveals how evangelical Christians interpret what is going on.

I know that my observations here are nothing original. The millennial underpinning of evangelical Christian support for Israel is something many have explored. The new piece for me, personally, is the recognition that my upbringing within evangelical Christianity and the cultural capital that has given me demands my action. As someone who came out of this tradition and who is now a biblical scholar, I have an obligation to call out these perspectives as inherently antisemitic and contributing to the oppression of Palestinians.

Instead of “praying for Israel,” I will work to combat antisemitism in all its forms, especially Christian antisemitism. I will support those working for peaceful solutions for coexistence in the Middle East, like those Israeli Jews working together with Arab Israelis who believe continued attacks on Gaza and aid restrictions are counter-productive and immoral.